Amanda Burgan

Copywriter

Late last September, my parents and I boarded a so-called fast boat to the tiny island where they set up a sea farm 35 years earlier. Siquijor is located in the Central Visayas region of the Philippines. With a 63-mile coastline, it’s the third smallest province in a country made of over 7,000 islands, and among Filipinos, best known for its mangos, witch doctors, and general remoteness. When my parents lived there, for example, there was no electricity. Instead they used kerosene lamps, open windows, and a lot of mosquito netting.

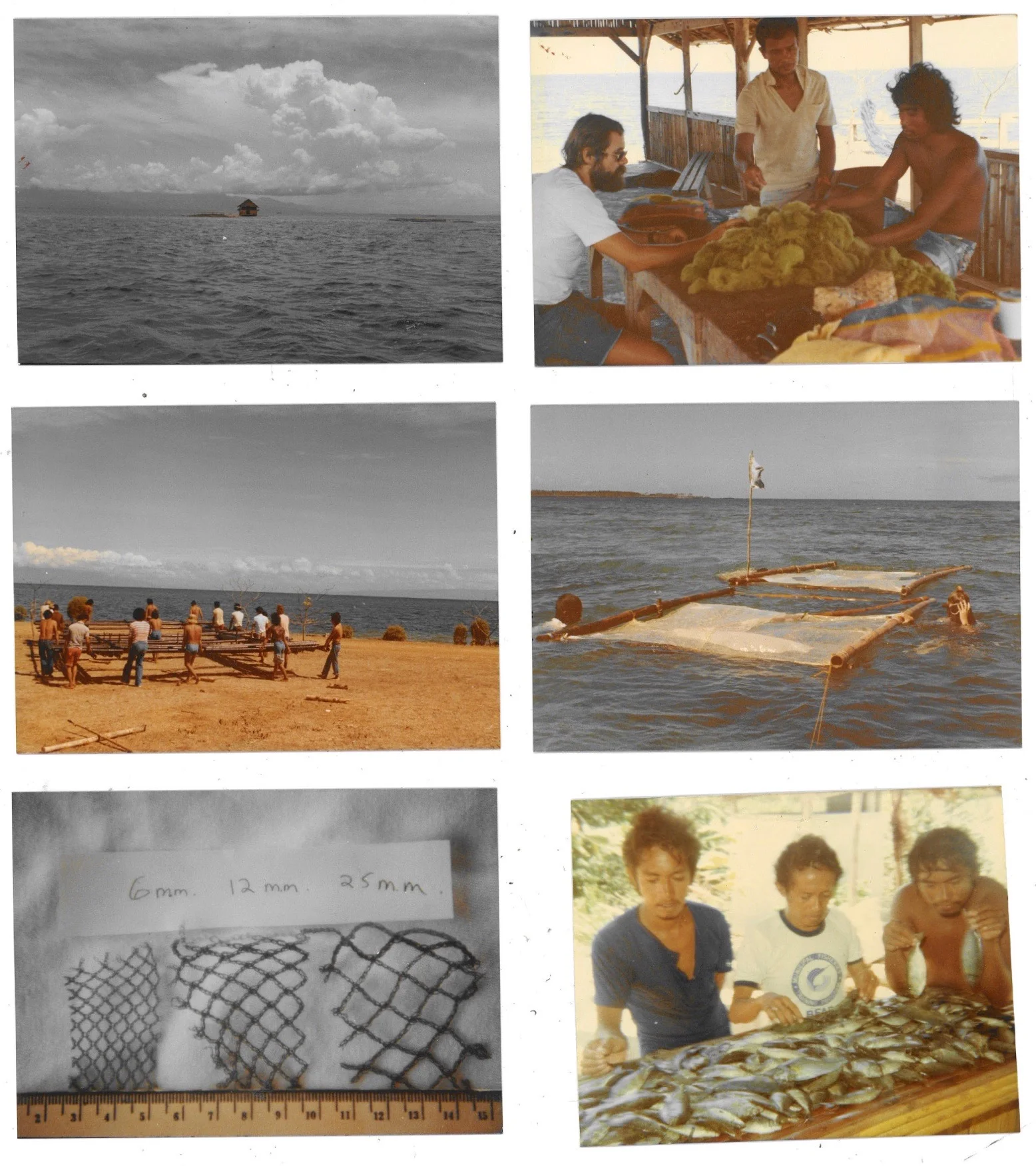

On this trip, their first time returning since 1977, my mom brought along a photo album. Inside were pictures of her and my dad: twenty-something, tan, and busy building floating fish cages. She brought it (I think) to recall having been so young with their fellow volunteers, who we’d reunite later on a different island. In the meantime though, it became our ticket to this one.

Photo album in tow, we set out with Bibi, the cook and driver at the hotel where we stayed. Translating for us as we inched through villages in a dusty minivan, he was able to track down three of the faces in my mom’s photos: Felisardo ‘Sardo’, a onetime fisherman and now local politician; Anastasia ‘Tasing’, my mother’s language teacher; and Amada, the daughter of William, a once good friend of my parents. Each had no idea we were coming but recognized my parents after only a few moments and welcomed us with warm excitement. We talked about what everyone had been up to, looked at scrapbooks filled with photos of children and grandchildren, and met cats. Then, after a morning spent catching up, we made our way to the sea farm site.

Rabbit fish fingerlings (about the size of your pinky nail) are abundant year-round in the Philippine Sea and caught by the millions to make fish paste and sauce. The fish can also be caught at two-inches long and fried crisp like a potato chip. But a grown rabbit fish is the ideal catch, as it provides an individual-sized meal.

During typhoon season it can be difficult to catch enough sizable fish to support the island, which is why my parents originally came to Siquijor, by way of the Peace Corps, to help. They proposed a farming system that would raise grown fish from fingerlings in sheltered lagoons and eventually began construction on two 20 x 30 ft. fish cages, plus a floating rest house to eat lunch in and escape the sun.

With the help of local fishermen, both cages were divided into three sections — successively larger and deeper to account for the different growth phases — and then anchored a half-mile off the northwest coast. They created a fish food made from boiled leaves of ipil-ipil trees and monitored their fingerlings daily. Within three months the fish were hand-sized and ready to bring to market. Their project was a success.

Growing up, my parents’ Peace Corps experience was delivered to my sisters and me in anecdotes. They’d throw in Filipino phrases on a car trip or at the dinner table, but more or less stuck to the highlights restless children sit still for — like the time my mother was stung by a scorpion, or my dad’s visit to a witch doctor after a motorcycle accident supposedly caused by a jealous forest-spirit. (The spirit one really got us.) I’d probe them here and there as I got older, but it wasn’t until the first stop on our drive, Sardo’s, that I got a real sense of their contribution.

Sitting in his airy, one-story house, snacking on mangos and watching my parents chat with old friends about their struggle to procure a meter stick, I thought about what volunteering on a remote island in the seventies must have been like.

I listened and looked at the notes on the backs of my mom’s photographs to learn more about a fish called rabbit.